This year is László Lovász‘s 70th birthday and I went to his birthday conference, so a blog post about one of his famous results seems to be appropriate: the chromatic number of the Kneser graph.

Let be a graph with a vertex set

and an adjacency relation

. A coloring of

is a map from

from

to a set of colors

such that no pair of adjacent vertices gets mapped to the same element of

. The chromatic number of

is the smallest number of colors needed to color

. One of the nicest graphs to investigate is the Kneser graph: Here

consists of all subsets of

of size

and two vertices are adjacent if the corresponding

-sets are disjoint. For

and

, this is the famous Petersen graph:

It is well-known that we can color the Petersen graph with 3 colors, but not with 2 (because the graph contains 5-cycles), so the chromatic number is 3:

When we increase by one to

, then we need

colors. Now if we increase

from

to

, then the resulting graph is bipartite an the chromatic number is obviously

. In general: When we increased

by one, then the chromatic number increased by one, and when we increased

by one, then the chromatic number decreased by

. Martin Kneser conjectured that the Kneser graph always behaves like this (a long as

), so that the chromatic number is

. This was shown by Lovasz in 1978. Nowadays many different proofs of the Kneser’s conjecture are known. The significance of Lovasz’s result lies in the fact (besides solving the problem) that it relies on a topological statement, the Borsuk-Ulam theorem, and, therefore, gave rise to topological proofs in combinatorics.

One can define a -analog of the Kneser graph: Here our vertex set is the set of

-subspaces of a finite vector space of dimension

over a finite field of size

. Two vertices are adjacent if and only if their intersection is a subspace of dimension

.

For Blokhuis, Brouwer, Chowdhury, Frankl, Mussche, Patkós, and Szőnyi showed that the correct answer is

. Their proof does not involve

and

, but one can fix this with other techniques. In another paper Blokhuis, Brouwer and Szönyi showed that for

(remember, this was a boring question for the set case!) the answer is

as long as

. I recently showed that one can drop the condition on

and just require

(most likely

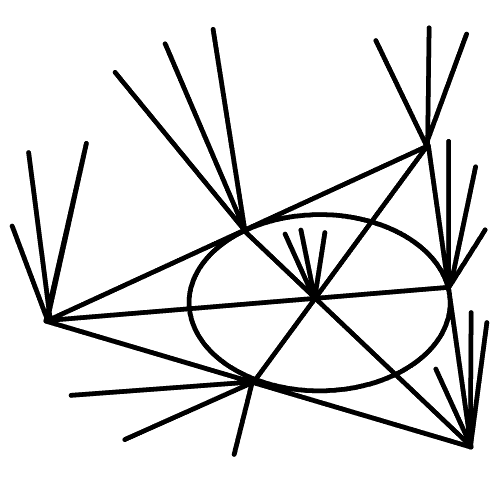

, but this I could not show). In the following I want to spent some time on explaining how the proof by Blokhuis et al. works. For

,

, and

the following image gives an idea on how the structure of

-spaces in graph looks like. The vertices are the lines and two lines are adjacent when they do not meet (so intersect in dimension 0). Our picture here is incomplete as we only show a

-space, a Fano plane, and some of the lines meeting it.

For any coloring the vertices with the same color are pairwise non-adjacent, so they form an independent set. Hence, the maximum size of an independent set of a graph with

vertices gives the lower bound

on the chromatic number of the graph (at least for a vertex-transitive graph). Now it could be that we are not using our largest independent sets (or subsets of them) for all of our colors in the graph, but then our lower bound on the chromatic number gets better than

. One standard way of determining the chromatic number of a nice graph (such as the

-Kneser graph) is to show two things: (1) One characterizes the structure of the largest independent sets. (2) One shows that all independent sets, which are not contained in the largest ones, are much smaller than the largest independent sets. If (1) and (2) are both true, then we are in a good situation: As soon as we use independent sets which are not the largest ones, then, due to (2), our bound on the chromatic number gets much better, so we are good.

In the -Kneser graph, even for

, the situation is good. The largest independent sets (sets of pairwise intersecting

-spaces) have size

— this is the number of

-spaces containing one fixed

-space or lying in one fixed

-space — , while the the second largest maximal independent set is smaller by a factor of

as long as

is a bit larger than

. For an example take

. We can easily color the

-Kneser graph in

colors as follows (we will use projective notation for this, so a

-space is a point, a

-space a line, and a

-space a plane): Fix a plane

. Take a line

in

. For each plane

through

with

we assign one color to all lines in that plane. There are

planes like this. This assigns a color to all lines not in

which meet

. We still have to color all lines which meet

in a point in

. There are

such points. For each of these we assign a color to all lines incident with that point. Now we have used

colors and all lines got (at least) one color as they all meet

. Here is a picture for

:

Now suppose that we find a coloring with less than colors. If we only use points and hyperplanes for coloring, then suppose that there is a line

which is not colored by any plane and colored by exactly one point

. There are

lines

which meet

in a point, but do not contain

. A point not in

colors at most

lines of

, the first hyperplane containing a point

colors at most

lines of

, while each subsequent hyperplane on $r$ colors at most

lines of

. If we color

with

points and

hyperplanes, then this gives that we color at most

elements of

with these. Hence,

. Therefore, we need

colors in total. In this special case, there are no other maximal independent sets (one could say, the next smallest example has size 0), so the chromatic number is

. For larger

, this is not the case and the complicated part is to bound size of the second largest intersecting family.

Thanks for explaining your article! You mention that this technique works for vertex-transitive graphs, I guess similar techniques would work for other classical DRG’s? Some typo’s I encountered along the way:

– I think you forgot to delete some words in the second sentence of your second paragraph a bit smaller than 2? 😉

a bit smaller than 2? 😉 , I guess this should be $q^2+q$?

, I guess this should be $q^2+q$?

– in the second paragraph under the third picture, you forgot a `latex’ for the $k$. I also find it hard to find a prime power

– lastly, under the last picture you mention the bound

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your corrections.

On your question: Yes, the same argument should work for more distance-regular graphs. For example I know how to show it for dual polar graphs with . Bilinear forms graphs might be an easy target too as EKR theorems are known there. Of course there are DRGs without any EKR theorem, so at least this approach does not work.

. Bilinear forms graphs might be an easy target too as EKR theorems are known there. Of course there are DRGs without any EKR theorem, so at least this approach does not work.

LikeLike